Warning: This review contains spoilers for the book and the movie.

For the past three decades, the Star Wars franchise has set the bar for sequels: like The Empire Strikes Back following A New Hope, second films in a series aspire to match the first in intensity and quality. Usually they fall short, frequently by a significant margin. With Catching Fire, the second film in the four-movie series, The Hunger Games franchise has delivered a worthy sequel – one that matches, and sometimes exceeds, the first film.

The movie opens with visuals that quickly establish the tone of the story ahead. It is winter; the life and warmth have been sucked out of Katniss’ surroundings. She stares off into the distance, unsure of the ramifications of her choices and what the future holds. Her mind is still deeply affected by the post-traumatic stress of the Games: the snap of a twig causes her to draw her bow on an approaching Gale; an arrow fired at a wild turkey brings back memories of slaying Marvel in the arena. From Gale’s reactions, instantaneously calm and reassuring, it’s clear he’s experienced these moments with her many times before. Later, Haymitch tells Katniss that the Games have no winners, only survivors. From the opening minutes it’s clear that for Katniss, surviving life as a Victor is equally challenging.

The movie opens with visuals that quickly establish the tone of the story ahead. It is winter; the life and warmth have been sucked out of Katniss’ surroundings. She stares off into the distance, unsure of the ramifications of her choices and what the future holds. Her mind is still deeply affected by the post-traumatic stress of the Games: the snap of a twig causes her to draw her bow on an approaching Gale; an arrow fired at a wild turkey brings back memories of slaying Marvel in the arena. From Gale’s reactions, instantaneously calm and reassuring, it’s clear he’s experienced these moments with her many times before. Later, Haymitch tells Katniss that the Games have no winners, only survivors. From the opening minutes it’s clear that for Katniss, surviving life as a Victor is equally challenging.

Symbolism is used effectively throughout the rest of the film, as well. Visibly more mature, Prim symbolizes District 12 itself. In the first movie, she was meek and uncertain; now she is bolder and more confident. When Katniss expresses her fear that her actions will come back to hurt her sister and mother, she means all of District 12 too; when Prim responds “We’re with you,” she speaks not just for the Everdeens but for all those in the District, like Gale and his colleagues in the mines, who now have the hope to stand and fight for a better life. Similarly, Effie’s progression in Catching Fire represents the Capitol: at first excited for the Victory Tour and another Games, then in shock at the revelation of the Quarter Quell’s tributes, and lastly beginning to finally see the injustice and tragedy of the Games in the fates about to be inflicted on the Victors. The symbolism of that tyranny peaks when Katniss twirls her wedding dress, it burns into black, and her wings rise to form a mockingjay. In this act of defiance, Cinna reminds everyone in the Capitol that Katniss won’t get the happily ever after that had been promised to her – and to her adoring admirers, who become doubly shocked when Peeta drops his “baby bomb” a few moments later in the broadcast. Cinna equally reminds everyone in the Districts that no happy ending awaits them either, unless they’re willing to join the Mockingjay and fight for it. Even the Christ symbolism, sometimes very heavy-handed in movies like Man of Steel, is reserved for subtle moments like the crown of thorns on Katniss’ head and the splay of her arms while being raised into the light from the overhead rebellion hovercraft.

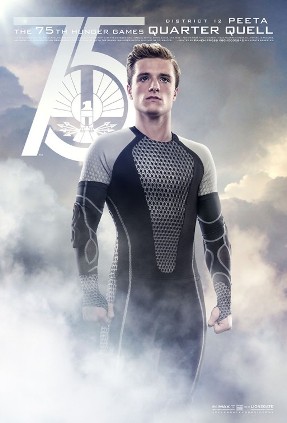

As in The Hunger Games, the cast of Catching Fire once again turns in acting performances of the highest level. The returning principals – including Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Woody Harrelson, and Liam Hemsworth – are outstanding. The supporting players like Elizabeth Banks, Donald Sutherland, and Lenny Kravitz continue their remarkable portrayals from the first movie. The two most prominent newcomers, Sam Claflin as Finnick Odair and Jena Malone as Johanna Mason, channel their characters brilliantly. In the book, each character has a very memorable entrance: Finnick’s sultry offer of a sugar cube and Johanna’s brazen strip-down in the elevator. In the movie, both scenes are perfectly acted, bringing the characters to life onscreen just as vividly as on the page. Philip Seymour Hoffman as the ambiguous Plutarch Heavensbee and Jeffrey Wright as Beetee also warrant mention; both are spot-on in their portrayals.

In addition to all of the obvious favorite moments brought to life on the screen – the chilling conversation between Katniss and President Snow, the decadent party at the end of the Victory Tour, the sight of the twenty-four Victors holding their raised hands in the air in unity and defiance, the clock arena with its poison fog and spinning Cornucopia, and many others – the little touches in Catching Fire are equally powerful. When Gale is whipped, Mrs. Everdeen’s hands are shaking when she tries to prepare the morphling – but she is the first to raise the three-finger salute at the Reaping. The recast Buttercup makes three appearances, twice in Prim’s arms to emphasize just how much he really is Prim’s cat. Snow’s granddaughter is a brilliant addition to the story. Her fashion choice to wear her hair in a braid drives home for Snow just how dangerous Katniss’ popularity really is. Her genuine reaction to seeing Katniss and Peeta share a tearful kiss and embrace after his near-death at the force field draws an ironic smile from the President; perhaps Katniss has finally convinced him that her feelings for Peeta are real, but only after it is already far too late for any mercy to come to them. And of course the little moment of breaking the fourth wall: having Effie acknowledge the superior special effects in Catching Fire compared to The Hunger Games as a byproduct of the Capitol’s increased expenditures for the Quarter Quell, just as Lionsgate dramatically escalated the budget for the second film after the smashing success of the first.

The core of the Hunger Games franchise, though, is the characters. In Catching Fire the characterizations continue to shine. Katniss isn’t the only Victor with PTSD: Peeta admits to nightmares of his own, and Haymitch overtly admires the self-medicating addictions of the morphlings from District 6. All of the Victors fear losing loved ones: Finnick watches Mags sacrifice herself and fears the jabberjay calls mimicking Annie are copying her real cries; the only friends that Haymitch actually personally introduces to Katniss and Peeta are Seeder and Chaff from District 11, who both die in the arena. Yet the connection between Haymitch and Finnick is subtly hinted throughout, long before the ending revelation aboard the rebellion hovercraft. Even though Snow tells Katniss that her act with Peeta has fooled everyone in the Capitol, Finnick’s whispered sarcasm makes clear he knows the truth – and who else could have told him but Haymitch? The gold bangle is a clear sign to Katniss that she should use Finnick as an ally, but the depth of his connection to Haymitch is only truly clear when he repeats verbatim the same admonition: “Remember who the real enemy is.”

If Finnick’s loyalty is foreshadowed in hints, Plutarch’s motivations are kept completely inscrutable to anyone in the audience who hasn’t read the books. In his single conversation with Katniss, he calls the decadence “appalling” and makes no secret of how and why Seneca Crane was executed, yet also gives Katniss no specific reason to trust him – only the most oblique reference that he “volunteered” to lead the Games from being inspired by her example. To Snow he acts the part of a Capitol loyalist, making suggestions for how to undermine the incipient rebellion and Katniss’ fame as effectively as possible. Only at the very end, when his true allegiances are revealed, does his dialogue take on a whole new light. In hindsight, every line he exchanges with Snow is actually about the rebellion. He speaks of “moves and countermoves” heading into the Games; the “wrinkle” of the Victors being reaped for the Quarter Quell is a spark for defiance by the Victors and outrage by the public. When Snow tells Plutarch that the Victors aren’t playing his game, the opposite is actually true, at least for some. And most ironic of all, Plutarch says of Katniss “that’s our girl” in his final conversation with Snow. The Head Gamemaker is playing a very dangerous game indeed.

Catching Fire also makes several important moves to set up Gale, Peeta, and Katniss for the events set to unfold in the two Mockingjay films. The opening scenes reestablish that a life with Gale is what Katniss’ heart truly wants. With him, in the woods and helping their families, is where she wants to be. Unfortunately she soon learns that she’ll “never get off this train” in the life she forged as a co-Victor with Peeta. That causes her to default to her core motivation: protecting those she cares about. Her first reaction is to run away, to save their three families from Snow’s wrath. Gale, though, sees a bigger picture: even if their small circle could run away, the rest of District 12 would continue to suffer. He is ready to stand and fight, then proves his intentions by attacking a Peacekeeper and getting whipped for his effort. Gale understands that rebellion means lives will be lost and suffering will occur, but Katniss wants to take on all of the risk herself to keep others out of harm’s way. This difference of perspective will only grow greater.

Prior to the release of Catching Fire, director Francis Lawrence explained that Peeta would take a more active role in the second movie compared to the second book. His choice of words – saying that the script had “manned up” Peeta – drew some controversy and raised concerns that Peeta’s characterization might differ too much from the books. In the final film, though, the character retains very much the same core. In the book, Katniss’ first-person point-of-view narrates the story, and her primary motivation once the terms of the Quarter Quell are announced is to keep him alive. She is attuned to his weaknesses and vulnerabilities, perhaps exaggerating them in her thoughts from her fear of failure. In the movie, by contrast, the audience sees Peeta as he is, unfiltered by Katniss’ perceptions and intentions.  Although he has moments of vulnerability, such as colliding with the force field and being afflicted with the poison fog, he may be more capable than Katniss herself realizes. In the books, the principal characterization beats for Peeta involve establishing the personality traits that Katniss comes to love in him: his kindness, compassion, generosity, and selflessness. The Catching Fire movie hits all of these beats across Peeta’s story: he sits with the recovering Gale despite knowing how Katniss feels about him; he initiates their conversation about working to at least be friends rather than emotionally distant; he holds Katniss in bed after her nightmares; he paints an image of Rue as his own act of defiance against the injustice of the Games; he accepts the idea of a sham quickie wedding for publicity purposes; he comforts the dying morphling in the arena. Most of all he gives Katniss the locket with pictures of her mother, sister, and Gale, driving home the point that he wants Katniss to be happy even if that means he is unhappy (or dead). That selfless act resonates with Katniss so deeply that she gives him the first true romantic kiss between them, rather than a kiss staged for the public or in reaction to his shocking near-death.

Although he has moments of vulnerability, such as colliding with the force field and being afflicted with the poison fog, he may be more capable than Katniss herself realizes. In the books, the principal characterization beats for Peeta involve establishing the personality traits that Katniss comes to love in him: his kindness, compassion, generosity, and selflessness. The Catching Fire movie hits all of these beats across Peeta’s story: he sits with the recovering Gale despite knowing how Katniss feels about him; he initiates their conversation about working to at least be friends rather than emotionally distant; he holds Katniss in bed after her nightmares; he paints an image of Rue as his own act of defiance against the injustice of the Games; he accepts the idea of a sham quickie wedding for publicity purposes; he comforts the dying morphling in the arena. Most of all he gives Katniss the locket with pictures of her mother, sister, and Gale, driving home the point that he wants Katniss to be happy even if that means he is unhappy (or dead). That selfless act resonates with Katniss so deeply that she gives him the first true romantic kiss between them, rather than a kiss staged for the public or in reaction to his shocking near-death.

All of the traits in Peeta that Katniss finds attractive are present in the film – and none of them are undercut by making Peeta more physically skilled than his counterpart in the book. Having not lost a leg in the previous Games, Peeta is capable of drowning a rival Victor in the opening sequence, leading the trek into the jungle, and effectively wielding a sword to fend off the attacking muttation monkeys. Peeta is more on par with the other Victors, yet his personality remains unchanged. In that sense, perhaps the movie actually sends a better message to the audience – particularly young people in the audience, boys and girls alike – than the book version of the character. In the books, Peeta makes the “sensitive” young man a viable option, even if he is weaker physically compared to “tough” guys like Gale or Finnick. In the movie, Peeta is both physically capable and driven by the same compassionate and selfless emotions as his book counterpart. In the real world and in fiction, we could use more young men who break down the supposed dichotomy between physically gifted and emotionally intelligent as options for men. By dissociating Peeta’s emotional core from his physical weakness, the Catching Fire movie actually makes him a better role model – in a series that already presents a great one in Katniss Everdeen.

The movie ends with a silent focus simply on Katniss’ face, as Jennifer Lawrence conveys the transition from grief at the news of the fate of District 12 to burning anger. But that anger is not just at Snow for what he has done to her home and its residents. It is no coincidence that Katniss learns the news from Gale. Early in the film, Gale confronted her with the reality that saving themselves by running away would only leave everyone else behind to suffer. In starting the revolution with the escape from the arena, Haymitch and Plutarch have done exactly that: saving themselves, and Katniss as their precious symbol of the rebellion, and leaving everyone else to the suffering inflicted on them. And they did so without giving Katniss any choice in the matter, or the residents of District 12 a choice whether to take on that sacrifice for the greater good. Katniss’ rage at Snow is paired with betrayal by the rebellion’s new leaders – and both of those emotions will come to the fore in Mockingjay.

9.5/10